Supplementary information for Altermatt et al. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. DOI: 10.1111/2041-210X.12312

“Big answers from small worlds: a user's guide for protist microcosms as a model system in ecology and evolution”

Altermatt F, Fronhofer EA, Garnier A, Giometto A, Hammes F, Klecka J, Legrand D, Mächler E, Massie TM, Pennekamp F, Plebani M, Pontarp M, Schtickzelle N, Thuillier V & Petchey OL

2.9 Respirometry

Introduction

Respirometers are devices that measure respiration rates of individual organisms or collections of organisms (e.g., community respiration). They can also be used to measure gross photosynthetic rates when used in conjunction with light-bottle-dark-bottle experiments (e.g., Petchey et al. 1999). Respirometers are regularly used for microbial respiration often of environmental soil and water research; food science and preservation; insect respiration; tissue and skin respiration; plant primary production, and a wide range of other applications.

Various technologies exist, though most rely on the consumption of oxygen and or production of carbon dioxide that accompanies respiration, and that rates of consumption are linearly related to rate of respiration. Indeed, respiration rates are usually given in units of amount of oxygen per time (e.g., Fenchel & Finlay 1983).

Technologies for measuring gas concentrations include: oxygen cells, infrared CO2 sensor, colorimetry, optodes, polargraphic / electrode dissolve oxygen sensors, and manometry. A respirometer is one of these technologies, which embeds a sensor for gas concentration measurement in a sample, containing a culture of organisms. Many such devices exist. For measuring dissolved O2 concentration with electrochemical sensors see (Pratt & Berkson 1959). For measuring CO2 concentration within four to six hours based on colorimetric detection, using MicroRespTM, see (Campbell, Chapman & Davidson 2003; Campbell & Chapman 2003).

This document may develop into a list of detailed protocols for each technology and device, in which there would be some overlap with the device’s manufacturer manuals. Here, we provide an overview of different available technologies and mention some of the devices that adopt them, listing their advantages and disadvantages. Note that measuring gas concentrations often requires accounting for pressure, temperature, salinity, and pH.

Materials

Equipment

Oxygen cells and infrared CO2 sensors

These technologies provide a measurement of the concentration of oxygen or carbon dioxide in a sample of gas. This sample of gas typically comes from the headspace above the liquid in a culture vessel. The gas composition and changes in gas composition of the headspace reflect production and consumption of gases by the organisms in the liquid. Rates of evolution of oxygen are calculated from the rate of change of oxygen in the headspace.

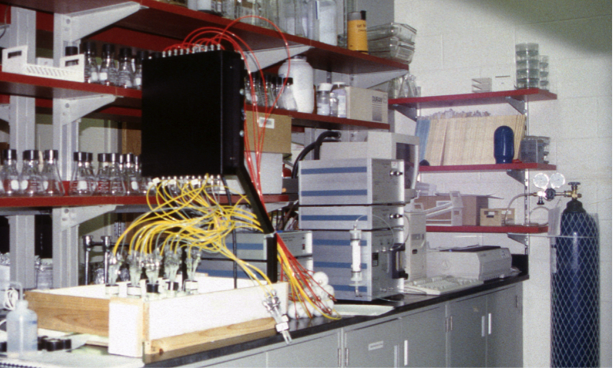

Devices employing this approach need some method of sampling the headspace, and often this must involve the headspace being sealed from the atmosphere. Sealing the headspace for long periods can cause large changes in dissolved oxygen and carbon dioxide concentrations. An example device is the Micro-Oxymax Closed-Circuit Respirometer manufactured by Columbus Instruments. This device has many settings, including the option to refresh the headspace with atmospheric gas, to avoid large deviations in dissolved oxygen and carbon dioxide concentrations. The system automatically compensates for changes in pressure and temperature. It also has the option to multiplex multiple vessels (up to 80) into one respirometer, so that respiration of multiple microcosms can be simultaneously recorded.

Oxygen cells have limited life, must be regularly calibrated, should not be exposed to moist gases. Care must be taken to assure there are no leaks in gas pipes. We have found that a closed circuit respirometer is the type of device that performs best if one lab member has sole responsibility to maintain and operate it, but requires considerable training for each user. Consumables include: oxygen sensors and compounds for extracting moisture from gas.

Fig. S1. A Columbus Instruments Micro-Oxymax Closed Circuit Respirometer. Culture vessels are in the wooden tray (lower left). Yellow tubes take gas from the headspace of the culture vessels through the black guide box to the silver and blue striped pump, dryer, and measurement boxes. The blue gas cylinder contains calibration gas. Photo by Owen Petchey.

Colorimetry

This technology involves oxygen or carbon dioxide causing a chemical reaction that then results in colour change in a substance. This colour change is quantified and transformed into a measure of respiration rate. Several chemical reactions can be used, and these are embedded into various devices.

An example is the microplate-based respiration MicroRespTM device, which can measure respiration rate in 96 samples simultaneously. The device consists of disposable 96-well plates and a spectrophotometer microplate reader. Samples must be taken and placed in the device, and provide an estimate of the respiration rate of organisms in that sample. Any changes in composition or abundance of organisms during the colorimetry will cause deviation between the respiration in the microcosms and that measured by colorimetry.

Fig. S2. A MicroRespTM starter kit (image from http://www.microresp.com/micro_order.html).

Optode sensors

Optodes, also called chemical optical sensors, are a relatively new tool measuring environmental variables, such as gas concentration in liquids and gases. The optode is stuck on the inside surface of a culture vessel, and is read by a fibre optic cable placed on the outside of the culture vessel. The fluorescence read by the fibre optic cable is related to the concentration of dissolved gas (e.g., oxygen, carbon dioxide). Measurements are relatively fast (a couple of seconds) and require minimal training of personnel. Apart from the presence of the optode, there need be no disturbance associated with measurements. Calculations are required to transform gas concentrations into measures of rates of gas production / consumption.

Fig. S3. Left: A sensor (optode by PreSens GmbH) glued to the inner surface of a standard culture vessel. Right: A measurement of oxygen saturation being made. Microcosms are fitted with a guide to ensure the fibre optic cable is correctly placed. Photos by Owen Petchey.

Polagraphic / electrode dissolved oxygen sensors can also be used to measure dissolved oxygen concentrations, which could then also be transformed into measures of gas production / consumption. Polargraphic oxygen sensors consist of anode, cathode, and electrolyte solution, separated from the sample liquid by a semi-permeable membrane. These are standard instruments for measuring dissolved oxygen and require that the sensor is dipped into the culture media, therefore care must be taken to prevent contaminations.

Manometer based measures

Manometer based measures involve placing the sample in a gas-tight apparatus that include a compound that absorbs carbon dioxide. Because carbon dioxide is absorbed, respiration results in reduced pressure within the apparatus. Therefore, the measurement of pressure changes, for example with a manometer rube, allows measuring respiration. More sophisticated apparatuses include a transducer for converting pressure into an electrical signal that is sent to a computer. As well as providing a digital measure of pressure change, this signal can be used to trigger oxygen production, so that the pressure and oxygen concentration in the apparatus remains constant. One limitation of this method is that organisms that require carbon dioxide will be negatively affected within the apparatus.

Procedure for Optodes

-

Choose culture vessels that are compatible with the optode technology, e.g., pyrex with thin enough walls.

-

Glue the optodes to the inside surface of the culture vessels at a specific position. Ensure that the glue is non-toxic for the organisms.

-

Calibrate individual optodes following manufacturers guides and methods.

-

Autoclave the vessels (optodes are unaffected).

-

Prepare the samples as required.

-

Place the culture vessels inside an incubator, to ensure constant temperature throughout the measurement.

-

Take a measurement as per the manufacturers instructions, ensuring that the microcosms are not moved before a measurement is made. Even small movements can affect measured dissolved oxygen.

-

Perform calculations to transform measures of dissolved oyxgen into measures of oxygen production rate.

References

Campbell, C., Chapman, S. & Davidson, M. (2003) MicroResp Technical Manual. pp. 40. Macaulay Scientific Consulting Ltd, Abderdeen.

Campbell, C.D. & Chapman, S.J. (2003) A Rapid Microtiter Plate Method To Measure Carbon Dioxide Evolved from Carbon Substrate Amendments so as To Determine the Physiological Profiles of Soil Microbial Communities by Using Whole Soil. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 69, 3593-3599.

Fenchel, T. & Finlay, B.J. (1983) Respiration rates in heterotrophic, free-living protozoa. Microbial Ecology, 9, 99-122.

Petchey, O.L., McPhearson, P.T., Casey, T.M. & Morin, P.J. (1999) Environmental warming alters food-web structure and ecosystem function. Nature, 402, 69-72.

Pratt, D.M. & Berkson, H. (1959) Two sources of error in the Oxygen light and dark bottle method. Limnology and Oceanography, 4, 328-334.